Sententia Bona, or What Makes a Good Motto?

Adelaide de Beaumont

The desire to identify ourselves with a pithy turn of phrase seems to be widespread in both time and place. Whether adorning a silk banner, providing text for an heraldic achievement, or just finishing an email with a bit of flair, mottoes and catch-phrases are as popular today as they were with our medieval counterparts. [1, 2, 3] Here follows a brief history of mottoes, a discussion of their various types, and some hints for creating (or appropriating) one or more for your own use.

The trouble with pinning down the origin of mottoes comes from the many types of motto found in history. Knowing the type of motto is critical if you want more than one motto, because while it is not unusual for the same individual to have mottoes of two different types, it’s less likely that they would have multiple mottoes of the same type. It’s also good to know the type of motto, because they tend to have different uses.

The Cri-de-guerre, or War-cry, or Hurrah for Our Side!

War-cries are likely the oldest form of motto; however, it is difficult to pin down dates, as it wasn’t very common for people to bother to write down what was said to rally the troops. The British royal motto, “Dieu et mon droit” (‘God and my right’) is said to date to Richard I’s victory at the Battle of Gisors in 1198, where he is recorded to have said, “Not we, but God and our right have vanquished the French at Gisors.” [4] The sentiment is very near the phrase from Psalm 113:9 (Vulgate numbering) which became associated with the Templars: “non nobis Domine non nobis sed nomini tuo da gloriam” (‘not to us, Lord, not to us, but to your name is the glory’). [5] It seems logical that an effective war-cry should be in a language most of the soldiers understand; while Richard’s nobles spoke French, most of their foot soldiers likely did not. “Dieu et mon droit” was probably a more useful battle-cry for later kings who had the opportunity to spread the phrase around and make it familiar to rank-and-file English soldiers.

The English nobles must have been shouting something, and evidently a dizzying array of somethings, because an Act was passed in 1495, “forbidding such war-cries as tended to promote discord among the nobility, who were enjoined thenceforth to call only upon Saint George and the king.” [6] So when Shakespeare has Henry V (III, i) use the war-cry, “God for Harry, England and Saint George!” he was correct for his own time, but possibly not for Henry’s.

Meanwhile in Scotland, battlefields were ringing with a different set of cries. The Scots made heavy use of the “sluagh-ghairm” (Gaelic for ‘host-cry’), which came into English use as “slogan”. [7] Evidently, the Scots were better at not confusing matters with multiple war-cries; a Scottish history from 1536 remarks, “that nane of thaim name thair capitane with ony uthir sloggorne, bot with the auld name of that tribe.” A slightly later history of 1578 notes, “Thay hard ane slughorne cryand on the gait in this maner ‘ane hammiltowne’, ‘ane hammiltowne’.” [7]

To this day, the most popular slogan style among Scottish families (non-Gaelic-speaking Scottish families are properly called families rather than clans) is an exhortation of the family name, e.g., A Douglas!, A Gordon!, An Innes!; the most popular style among Gaelic-speaking clans seems to be the name of an area or feature of the land, e.g. Loch Sloy! (MacFarlane), Clar Innis! (Buchanan), Dunmaglass! (MacGillivray). [8] Though some war-cries were adopted as mottoes, some were joined or supplanted by less martial words; in Scotland in particular, many achievements bear both a motto and a slogan. [9]

Words to Live By

The fashion of heraldry spread from France and England across Europe, and with it, the idea of actually writing down the family motto. In particular, the badge, which came into general use around the reign of Edward III (reigned 1327-1377), was often accompanied with words or phrases. [9, 10] While some adopted a cri-de-guerre, some decided it was time for higher thoughts. Where the cri-de-guerre was normally in the owner’s spoken language, the motto was frequently in Latin or in another language in order to make it less obvious. Mottoes might appear on badges, seals, or even written across a shield.

Germans seem to be unique in their occasional use of a riddle motto, i.e., only the first letter of each word is inscribed. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III (1415-93) had the letters AEIOV inscribed in a number of places without choosing to tell anyone precisely what he meant by it, or even what language he intended. [12]

Mottoes also appeared in portraiture. A portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (attributed to Isaac Oliver, painted circa 1600) shows the queen holding a rainbow, and over the rainbow is the inscription “non sine sol iris” (Latin for ‘there is no rainbow without the sun’). [13] Personal mottoes appeared on furniture and other personal items, but some items rated their own motto; sundials in particular were often inscribed with a motto regarding the nature and effects of time. [9, 14]

Writing on the Sealing

One of the best sources for information on mottoes comes from personal seals. Members of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy were using personal seals by the end of the 11th century, and the practice spread rapidly. [15] Initially, seals typically bore only inscriptions like “Sigillum Gileberti de Clara” (‘Gilbert de Clare, his seal’ used in 1218), but before long other words and phrases appeared [16]. Some seals seem to have been early attempts at spin doctoring; Sir John de Byron used a seal with the words “Crede Beronti” (‘Trust in Byron’) in 1293. [17]

Like sundials, seals were viewed with near personhood, and mottoes were often written as if they were spoken by the seal. Isabel, countess of Gloucester (ca. 1189-1217) inherited a seal from her father depicting an eagle and inscribed “Aquila sum et custos comitis” (‘I am the eagle and guardian of the earl’); she had the inscription changed to “Ego sum Aquila custos domine mee” (‘I am the eagle, guardian of my lady’). [16] Inscribed mottoes could be romantic, like “Je su sel de amur lel” (‘I am the seal of loyal love’– I hope this seal was only used on love letters!). They could be religious; “ave Maria gracia plena” (‘Hail Mary, full of grace’) was quite popular. They could also indicate a certain lack of seriousness by the owner; a shocking number of medieval seals feature a picture of a squirrel and some variation on the statement “I crake notis”, perhaps indicating that the owner didn’t do much documentary business and had therefore found a better use for a large, heavy implement like a seal. [16, 18]

Some mottoes were designed as puns on the family name, for example, the Fortescue motto of “Forte scutum salus ducum” (‘a strong shield saves its commanders’) and the Seton motto of “Set On”, both of which are modern. “Ne vile velis” (‘desire nothing evil’, ‘not vile is thy will’), on the other hand, has been used by the Nevil(l)e family since at least 1600. [19] Most medieval puns alluded to the name more loosely, like Thomas of Fishburn’s “her is none bot a fische and har” (the seal shows a fish and a hare). [18]

Commemorative Phrase

The catch-phrase, an amusing, oft-repeated line (often from movies or television, e.g., “Wherever you go, there you are”) was obviously scarce in the medieval period; there was no mass media, and even among the literate you couldn’t be sure that everybody was familiar enough with the source to get the joke. (It wouldn’t shock me to see a line from Shakespeare used as a late-period motto, but I’ve never found an example.) There do seem to be mottoes that are meant to be self-effacing or humorous, from “I mene wel” to “bi the rode wimen ar wode” (‘by the Cross, women are mad’). [18]

A phrase that invoked a real-life incident was fair game. The most famous example is undoubtedly the motto of the Order of the Garter, “Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense’ (‘Shame be to whomever thinks evil of it’), which supposedly was spoken by Edward III (1312-1377). According to legend, while Edward was dancing his partner’s garter fell off, exposing her to ridicule. Edward gallantly placed the garter around his own leg, speaking the now-immortal words. [20] Another example is the motto originally connected to the La Warr family and now used by several subsidiary families, including West and Sackville: “Jour de Ma Vie” (‘Day of my life’). It was adopted to commemorate the capture of Jean II of France in the battle of Poitiers by Roger La Warr. [9] Capturing your enemy’s king in battle probably would be the day of your life for most knights!

The problem with commemorative phrases is one of public relations; you have to have something to say that is famous enough for people to recognize as significant. And if you intend the motto to be passed on to future generations, you’d better make sure they’re in on the joke. The Dakyns family of Derbyshire bears an armorial motto, “Strike, Dakyns, the devil’s in the hempe,” for which neither family members nor family historians have the slightest clue to its meaning. [4, 9]

A phrase must be specific enough to be “owned” as well, so while a phrase like, “No s#it, there we were” is recognizable as the beginning of a battle story, it can apply so equally to anyone in any interesting battle scenario that it has no value as a motto.

Picking a Language– The Case for English

As detailed above, if you intend your motto to be martial or humorous, or to recall an actual incident, it should be in the language you speak. If you do not speak or read any language other than English, consider sticking to English for your motto. English is very poorly suited to translation into other languages, especially Latin, chiefly because English long ago abandoned the concept of case. The grammatical case of a noun or pronoun indicates function in a sentence:

Case Example Latin form of “boy”

Nominative The boy is young puer

Accusative I saw the boy puerum

Genitive The boy’s house… pueri

Dative I gave the boy a ball puero

Thus, in Latin, we know immediately where a noun belongs in a sentence. In English, we have limited case change with pronouns; you (I hope) know that “I” and “she” indicate the subject of a sentence while “me” and “her” do not. We also use apostrophe-s to show possession (an abbreviation of the medieval ending –es, in case you were wondering). And that’s pretty much where we stop. Accordingly, we use word order and extra words (like prepositions) to force our sentences to make sense.

We’ve also grown remarkably lazy with verbs; most verbs have no more than two active forms, one to use with third person singular (he, she, it) and another to cover everything else. In Latin, the verb tells us a lot more about the doer:

First person singular I love amo

Second person singular You love amas

Third person singular He, she, it loves amat

First person plural We love amamus

Second person plural You love amantis

Third person plural They love amant

You can say “ego amo” (I love) in Latin, but “amo” conveys the same information, so the pronoun is frequently dropped. Between case identifiers on nouns and unique forms of verbs for each “person” it’s easy to see that word order becomes virtually irrelevant in Latin. Consider this common Latin motto:

Amor vincit omnia Love conquers all

Omnia vincit amor Everything is conquered by love

Vincit omnia amor Conquers everything, does love

(This is why Yoda sounds so odd. He’s so old, he’s thinking in Latin and translating on the fly, and being a lover of action, he favors putting his verbs first.)

You can’t change the basic sense by reordering the words. Amor is the subject of the sentence, and the verb indicates that something singular is doing the conquering (omnia is plural). If you wanted to say “everything conquers love” you have to change the phrase to Omnia vincunt amorum. Since the order doesn’t change the sense, order is often used for emphasis or poetic effect.

If you must have Latin or another language you do not speak, PLEASE consult someone who has studied the language rather than attempting to use Babelfish or other online translators. They can’t tell the difference between, say, the “her” in “her house” and the “her” in “I gave it to her”, which are different words in Latin. It may also offer you the closest match to a word without telling you, which is how my husband put in “two blades” and received a Latin phrase meaning “two bladders.”

Do NOT assume that Latin phrases in popular culture are correct. The people responsible are just as lazy as you are and probably had some flunky look online. This can lead to humorous errors. On one track of the Evanescence album “Fallen” the backup singers are supposedly singing “deliver us from evil” in Latin. Unfortunately, they forgot that the phrase “deliver us from” is poetically idiomatic and is more properly “save us from”. So they found the Latin verb for “to deliver” (meaning bring, like a pizza) and their singers are happily singing “bring us evil” for all they are worth.

Below, I’ve listed several websites which can generally be trusted for Latin and other mottoes. Have a look; someone else may already have said what you want to say.

Bibliography and Notes

[1] In case you care, ‘motto’ was borrowed from Italian and means ‘word.’ According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the correct plural is the same as it is in Italian, which is ‘motti.’ American English usage acknowledges both ‘mottos’ and ‘mottoes’ as correct plural forms.

[2] The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, s.v. motto. The earliest citation of the word ‘motto’ dates to 1589; Shakespeare also used it in Pericles, Prince of Tyre published in 1608. Both works mentioned mottoes in conjunction with descriptions of heraldry.

[3] Webster’s Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language. New York: Portland House, 1989, s.v. motto.

[4] Gough, Henry. A Glossary of Terms Used in British Heraldry. Oxford: John Henry Parker, 1847, pp. 228-9.

[5] Latin Vulgate .com. WWW: Mental Systems, 2012.

http://catholicbible.online/side_by_side/OT/Ps/ch_113 accessed March 22, 2021.

There are variances in numbering of certain books of the bible which makes it impossible to line up the Douay and King James versions with the Vulgate; accordingly, this page offers a modern English translation.

[6] Gough, p. xix.

[7] OED, s.v. slogan. The word appears in English in 1513 spelled “slogorne” and went through many forms until it reached the modern “slogan”. One of the commonest forms was “slughorn,” which J.K. Rowling later used as the name of a professor who was rather too fond of his own importance.

[8] Fulton, Alexander. Clans and Families of Scotland. Edison: Book Sales, 1999, s.nn. Buchanan, Douglas, Gordon, Innes, MacFarlane, MacGillivray.

[9] Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles and J.P. Brooke-Little. A Complete Guide to Heraldry. New York: Crown Publishers, 1985, pp. 341-4. Modern Scottish heralds register mottoes as a part of a complete granted achievement, and they assume the motto will be passed down with the heraldry. English heralds, on the other hand, only register a motto on request, and generally view mottoes as personal and not inherited.

[10] Fox-Davies, p. 345.

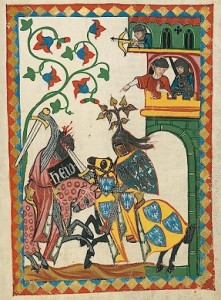

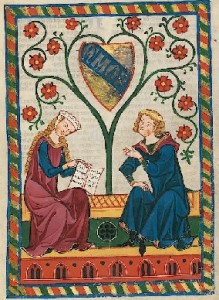

[11] “Manesse Codex” complete manuscript facsimile. WWW: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, 2012, plates 26r (recto, the right side of the sheet) and 311r.

https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848, accessed June 1, 2012

[12] Fox-Davies, p. 344. The motto has been translated in several different ways, including “Aquila Electa Iuste Omnia Vincit” (‘the chosen eagle vanquishes all by right’) and “Aller Ehren Ist Oesterrich Voll” (‘Austria is full of every honor’).

[13] “The Rainbow Portrait.” In Wikimedia Commons, WWW: Wikimedia, 2012.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Elizabeth_I_Rainbow_Portrait.jpg, accessed June 1, 2012

[14] Rohr, Réné RJ. Sundials: History, Theory, and Practice (translated by Gabriel Godin). New York: Dover, 1996.

[15] Harvey, P.D.A and Andrew McGuiness. A Guide to British Medieval Seals. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996, p. 43.

[16] Harvey, p.59.

[17] Gough, p. 227. The date is actually given as the 21st year of the reign of Edward I. Edward came to the throne in 1272, so 1272 plus 21 equals 1293.

[18] Harvey, Appendix: Legends on Personal Seals, pp. 114-119.

[19] Owen, John. Second Book of Epigrams, published 1606-1613, number 66.

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=eebo;idno=A53744.0001.001, accessed March 22, 2021.

[20] “Order of the Garter”. Encyclopedia Americana volume XII. New York: Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1919. p. 300.

If you would like me to help you with a motto, please email me at lisatheriot@ravenboymusic.com (or PM me on Facebook) and include the following information:

Your contact info

Your persona info (culture and period, if known)

The type of motto you want

The motto you are considering, why, and what you think it means

Websites I Recommend

The Vulgate Bible

http://www.catholicbible.online/

The bible in Latin is a source every medieval person had access to and familiarity with. This site has side-by-side Latin with the Knox Bible and the Douay-Rheims Bible. The New Testament portion of D-R was published in 1582, so it is a period English source for bible quotes.

Wikipedia—List of Latin Phrases

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin_phrases_(full)

Normally, I don’t recommend Wikipedia because of the variation in scholarship I find in the articles, but this is a good basic list, and seems to be taken from reliable sources. I would go to this page rather than Wikipedia’s “list of mottos” because the latter page has fewer phrases I would recommend in an SCA context. But hey, who knew Google’s motto is “Don’t Be Evil”? Also check “List of sundial mottos” for a nice collection of phrases concerning the nature of time.

Heraldic Latin Mottoes (Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Welsh Evidence)

http://www.yarntheory.net/ursulageorges/motto/welshmottoes.html

Symbols and Mottoes: The Renaissance Impresa

http://www.yarntheory.net/ursulageorges/imprese/imprese.html

Ursula’s scholarship is largely responsible for stimulating my interest in mottoes; we also share a hatred of the amount of bad Latin floating around SCA circles. Both these articles are well-researched and informative.

Vital Latin Phrases for Librarians

https://alecmuffett.com/article/354

If you MUST use a catchphrase rendered into Latin, this is a great source. The author is dry, cynical, and above all, well-versed in Latin. This is the place to go to find “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” and “The devil made me do it” in the language of the Caesars (among many other choice phrases).