Save the Trees!

Running an SCA

Lists on One Sheet of Paper

In the early days

of the

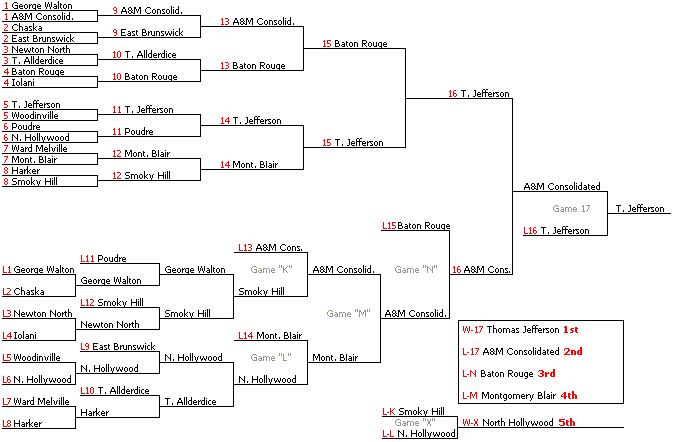

Let’s assume we’re

running a double-elimination tournament, and the following people sign up

for the lists:

| Belted: | Sir Rosis de Liver | Unbelted: | Edward Bell |

| Sir Ryosis

the Scaly |

John the Plain |

||

|

Mary Contrary |

|||

|

Sven Darkfalls |

|||

|

Uber Kuel |

|||

|

William Williams |

We can get started by writing each combatant’s name on a 3x5 card for use by the field heralds. (Always assume you will need 3x5 cards; the heralds may or may not have brought them!) This is a good time to get with the herald running the field and discuss whether the heralds will mark the cards (and whether they all have pens), or whether the winning combatant will return the cards to the lists table, or whatever method you agree on for conveying win-loss information from the field to the lists table.

This is also when you should check with the Crown, reigning Noble, or tournament sponsor as to how they would like the first round pairings to be determined, i.e. challenge, drawn by lot, fold, slide-and-fold, etc. (If any of these terms aren’t clear, there is a glossary at the end of the notes.) You should also ask whether, in a case like this with many more unbelted fighters than knights, they would like the knights “seeded,” that is, placed on the roster in such a way as to guarantee that they won’t fight each other in the early rounds. If the method is anything but a challenge, you can go ahead and enter the combatant information onto the grid sheet based on the pairings; otherwise, you’ll have to wait for the challenge to know who fights whom in round one.

Assuming we are going to seed the knights, the math is

simple: We have two knights out of eight combatants, so the knights will go in

at the 1st and 5th place (you want to make sure the knights are kept away from

the bottom of the grid—more on this later). After the challenges are done, John

will fight Sir Rosis, Edward and William will fight, Sven and Mary, and Uber

challenges Sir Ryosis. Based on these pairings, the names go onto the grid and

are assigned numbers as follows:

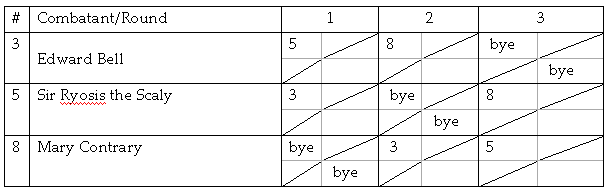

The grid boxes are split with a diagonal line; the upper portion shows the number of the opponent for that round, and the lower portion is reserved for a “W” or “L” to indicate wins and losses. You can always check your work by verifying the result against the opponent’s grid line—a W in the grid box for round one next to Sir Rosis’ names should correspond to an L in the grid box for his opponent for that round, in this case #2, John the Plain.

While the fights for the first round are going on, you can

fill out the pairings for the next round.

(Since this is double-elim, no one will be eliminated after round one.)

The method for pairing the second round which is least likely to cause

trouble later is to bring the bottom combatant up to fight #1; then 2 fights 3,

4 fights 5, and so on. This is why

you don’t want another knight at the bottom of the roster; they would have to

fight in round 2. (Why trouble?

If you start increasing the “reach”, i.e. 1 fights 4, 2 fights 5, etc.,

you’ll soon find you are lapping the list and it becomes much easier to make an

error.)

At the beginning of round 2, our grid looks like this:

We can’t do the pairings for round 3 yet, because we’re likely

going to lose fighters. With 8

fighters, you could be done in as few as 5 rounds if everybody dies according to

schedule, but plan for more, especially if you have several undefeated fighters

in the later rounds; ruling nobles like to spring “round robin” formats on you

at that point. (More on that

later.) Also, until you know how

quickly people die, you may not know in advance which round is the

“quarter-finals” and such. In

multi-elimination tournaments, the named rounds really don’t have much

significance, since you may have three rather than four fighters in the semis,

for example, but since fighters love to say, “I

Let’s assume that when the cards come back from round 2, John, William, Sven, and Mary have taken losses. That means that John and Sven have two losses and are out, so our remaining combatants are 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8. Starting at the top of the list again, 1 fights 3, but 4 has already fought 5 so we have to drop to 6, and 5 fights 8. The more fighters you have, and the later into the tourney you go, the more you may have to mix things around to keep people from fighting who have already fought. But you’ll be surprised how little it actually happens.

Don’t forget to scratch out the fighters with two losses so you don’t forget they’re gone!

Now let’s assume that in round 3, Sir Rosis, Sir Ryosis, and William all lost. This means William is out, and we are down to 1, 3, 5, 6, and 8—an odd number. Until the late stages of a tournament, you can bet that an odd number of fighters is going to mean a bye. You should talk with the ruling noble about whether the bye will be a gift or whether it will be fought, and whether that fight will be destructive (i.e., if you lose the bye fight, it counts as a loss just as if you had fought with an active combatant). Personally, I think destructive byes are cruel, since the “bye” is often a very accomplished fighter the likes of whom the combatant may not have faced in the early rounds of a tournament. It is a good way of knocking people out of a large lists more quickly, though. When it’s 100 degrees or the light is failing, cruel is good.

At

this point, you pray you have a clear winner.

If not, the tournament sponsor has to decide where to go from here.

Round robin was their bright idea, after all.

If, sadly, someone does have to withdraw, you simply treat that number as a BYE for the rest of the day. Scoring is based simply on number of wins and losses; if the tournament finishes with no clear winner, you may have to have a standard final round between the people with the fewest losses. Again, mercifully, this rarely happens.

The grid system is 100% percent flexible. If the tournament sponsor wakes up in a mood and says, “Okay, the tourney is triple-elimination with a fold pairing by height and I want to seed everybody whose name begins with S!” you can smile sweetly and say, “No problem!” When someone wants to pull out in the middle of the tourney for whatever reason, it doesn’t mess up a thing. I have included a master grid sheet with these notes, but notebook paper and a straightedge will get the job done in a pinch!

Questions of Philosophy

I hate trees for reasons beyond the staggering waste of paper. The idea of fixed brackets is inherently unfair. It can be a huge mental advantage to know who you’re going to face in later rounds (and who you’re NOT going to face). It may also be advantageous to wind up in the “loser’s bracket” because someone from that half is still going to be a finalist; is it fair to stack one side with demonstrably less skilled fighters?

If there are people that you’d like to keep apart, you can do it by the same method as seeding. If your tourney is in Seawinds and two guys have driven down from Namron, they’d probably rather not fight each other in the early rounds; slotting them in well away from each other is only hospitable. Likewise husbands and wives, etc. Obviously, in the later rounds, they take their chances with everyone else, but if the two guys from Namron are your finalists, I doubt they’ll mind.

When I was Kingdom Mistress of Lists for Caid, I used to get asked, “Can you ‘fix’ a tournament?” The answer is no. I can certainly make someone’s path harder or easier based on whom I throw in their way (when a fighter comes up against their third Duke in a row, they tend to come over to the table and ask how they have offended me…), but ultimately, the winner will still have to knock down a whole bunch of folks, who will themselves have had to knock down a whole bunch of folks to stick around. It’s one of the many advantages of using numbers for the fighters instead of names; you don’t have the slightest temptation to keep Mary away from Edward, you just know that 3 should fight 8 this round. And as long as you follow the rules, you can avoid even the suggestion of favoritism.

It’s not a bad idea, especially for a Crown Tournament, to have a bouncer. People will rush the table asking for information they can get elsewhere (like pairings) or simply to be nosy. If you like company, you will never lack for it, but if you’re trying to work out a tricky round or set up the cards for the heralds, you’d rather not deal with Lord Whatsits asking how many remaining fighters are undefeated.

When all else fails, blame the King. I mean this seriously. Your position as Lists Minister is neither to make controversial decisions, nor deal without the fallout thereon. When you are in any way unsure of the rightness of a pairing, bye assignment, request to keep certain people apart, etc., you can and should run it by the King (or sponsor). The opposite situation may also arise; the King may ask for things that you feel are inherently unfair, and you should feel free to say so. Fortunately, I have never had a King ask me do anything unfair that I was not able to talk him out of, but if he insists, he IS the King. Whether you comply is a matter for you to weigh against your own ideas of fealty and honor.

As the Lists Minister, I believe you have the responsibility to ensure that the selection of opponents is as fair as you can possibly make it, and the grid system is the best way I have found to accomplish that. The fact that is also simple and efficient is icing on the cake. So get thee to a Lists table and have fun!

Adelaide de Beaumont

Mka Lisa Theriot

Lnktheriot@satx.rr.com

Glossary of Common

Lists Terms

Bye:

“odd man out” combatant with no opponent for the current round.

May be allowed an automatic pass into the next round or may have to fight

an opponent selected by the sponsor.

From an adjectival use of the preposition <by> meaning ‘off to the side,

incidental.’

Challenge pairing:

combatants line up in two lines, and the

lower-precedence fighters challenge their choice from the higher-precedence

line.

Draw pairing:

the 3x5 cards are placed in a hat and pairs are drawn out at random.

Fold pairing:

combatants are lined up in order of precedence, and then “folded” such

that the highest ranking combatant fights the lowest ranking, and so on up the

line. If you numbered them by

precedence 1-8, 1 would fight 8, 2-7, 3-6, and 4-5.

Lists:

the field.

It’s always plural; it’s from a use of the word <list> meaning ‘edge’, as

in the selvage edge of fabric.

Since any two-dimensional area will have more than one side, “the lists” is the

correct term. If you drop the <s>,

you’d better set up your fighting field in a perfect circle.

Seeding:

Placing combatants in the grid or tree in such a way that they will not

face each other for several rounds.

Most often done with high-ranking combatants (knights, etc.).

Slide-and-fold pairing:

as in fold pairing, but the fold is

shifted by a few places. If there

is a three-place slide, for example, 3 and 4 will fight, as will 1 and 6, 2 and

5, and 7 and 8. Think of it as a

circle that gets squashed at the point of the slide.

Tree:

sometimes refers to a rack to hold s